Harold Wilson: ““I see myself as a big fat spider in the corner of the room. Sometimes I speak when I’m asleep. You should both listen. Occasionally when we meet, I might tell you to go to the Charing Cross Road and kick a blind man standing on the corner. That blind man may tell you something, lead you somewhere.””

Category: Uncategorised

Over-excited Clegg

Nick Clegg is now promising “

the most significant programme of empowerment… since the great enfranchisement of the 19th century. The biggest shake-up of our democracy since 1832, when the Great Reform Act redrew the boundaries of British democracy.

”

er…you don’t think there might have been a few important bits of empowerment since then, Nick? Like, votes for women? Or, for that matter, votes for non-rich men? Or education and healthcare; IMO the opportunity to be literate and not dead is reasonably empowering. I’m all for libel reform and regulation of CCTV, but they’re hardly comparable to universal suffrage.

Untitled

Cowardice, national and personal, allows me to present articles like this only if they’re safely enclosed in ironic bubble-wrap. Can’t think of any, so do it yourselves:

work hard, stay awake, fail well, hang with smart people, shed bullshit, say “maybe,” focus on action, and always always commit yourself to a bracing daily mixture of all the courage, honesty, and information you need to do something awesome

Self-tracking

This is a great NY Times article, very much in the tradition of bringing in whichever outside expert knows plenty about the subject, and (presumably) giving them very thorough editing for language and comprehensibility.

The subject is aelf-tracking, automatically gathering data about your health, mood, daily activities, storing it in a form which allows you later to analyze it and unpick the interactions between aspects of your daily life:

A hundred years ago, a bold researcher fascinated by the riddle of human personality might have grabbed onto new psychoanalytic concepts like repression and the unconscious. These ideas were invented by people who loved language. Even as therapeutic concepts of the self spread widely in simplified, easily accessible form, they retained something of the prolix, literary humanism of their inventors. From the languor of the analyst’s couch to the chatty inquisitiveness of a self-help questionnaire, the dominant forms of self-exploration assume that the road to knowledge lies through words. Trackers are exploring an alternate route. Instead of interrogating their inner worlds through talking and writing, they are using numbers. They are constructing a quantified self.

The project most interesting to me was one of the simplest, the moodscape mood-tracking system. And even there, it’s less for the interface itself than for the list of mood elements, which I may well incorporate into a spreadsheet and skip the online elements entirely.

Equality for economists

It’s a sad reflection on the state of our politics that nobody is mentioning how useful redistribution of wealth/income would be from a purely economic perspective, in stimulating increased spending &c. AG touches on it here. but there’s doubtless much better information elsewhere.

male-female-diff.PNG (PNG Image, 303×673 pixels) – Scaled (86%)

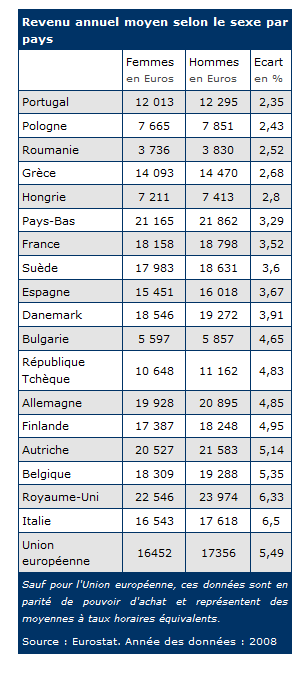

Within the EU, Britain has the second-largest income difference between men and women. Things are worse only in Italy:

male-female-diff.PNG (PNG Image, 303×673 pixels) – Scaled (86%)

AG on the burqa

AG on the burqa:

“Will a surveillance team stake out the Gare du Nord or the Sunday market at Cergy? Will Eric Besson and Brice Hortefeux accompany the flics as they lay hands on the offending ‘agent of Islamism?’ Will she be taken for a garde �vue and, in the name of equality of women and public security, be stripped of her robes and headgear, searched, photographed, and displayed on the evening news? Will she be hauled into court and required to appear with face uncovered before her ermine-clad judges? Will she then express gratitude to the state for emancipating her from her oppressive culture?”

Hunter S Thompson

My attitude to Hunter S Thompson is that of the owner of an overindulged rottweiler, calling him a harmless softie while barely restraining the beast. For sure, much of the HST mythos is true: doubtless he was a drug-addled psychotic bastard who you wouldn’t want to turn your back on. Posterity may have literally turned him into a cartoon — both

Transmetropolitan

‘s Spider Jerusalem and

Doonesbury

‘s Duke are based on him — but there was plenty of crazy lingering there from the get-go. Beneath it all, though, there’s a touching melange of disbaused idealism and a surprising affection for those working less dramatically from within the system.

Even

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

is, Duke keeps telling us, a search for the American Dream. The intrepid heroes purgatory their torsos, strain themselves to the point of breaking, and through this mortification uncover the nature of their world. The apparent nihilism is the aftermath of broken dreams, the realisation that the chnage which had appeared to be beginning in California in the 60s had come to a juddering halt:

[in the mid-Sixties] there was madness in any direction, at any hour. If not across the Bay, then up the Golden Gate or down 101 to Los Altos or La Honda….You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning.And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting—on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.

So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high—water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.

This sense of disappointed idealism, and the quest to regain it, appears much more strongly in

Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail

. his report from George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign. He’s striking in his affection for the young staffes and volunteers fighting for McGovern from within the system, even when their positions are far more centrist and pragmatic than anything Thompson would himself countenance.

Robot theology

While I’m on the subject of scholastics (I’ve just been listening to a lecture on the subject): had Ken Macleod been so minded, he could have found plenty o material in medieval theology to justify robot religion — perhaps starting with ideas of grace. In Aristotle’s conception, Grace is a form within the soul. That means it’s a shape, a pattern. The material in which it is embedded is irrelevant, just as a pot is a pot whether wooden or ceramic. Grace

in silico

would not be inferior to Grace

in vivo

**: robots would be as capable as humans of faith, hope and love.

* bear in mind, this entire concept remains somewhat new and alien to me; I’m almost certainly butchering some carefully-considered principle. In all honesty, I don’t much care.

** Doubtless you could concoct other arguments for robot inferiority, perhaps arguing that they weren’t created directly by good, and so are merely a shadow of a shadow of his Goodness. After all, Christians have plenty of experience justifying racism; justifying discrimination against machines would be an order of magnitude easier.

Science Envy

“Science envy” and “math envy” are perennial problems across huge swathes of the academic world. Mathematics and the hard sciences are seen as having achieved great leaps forward in understanding the world, and thus become objects for emulation whether applicable or not. Greek symbols start to fill up journal pages. It doesn’t matter if they demonstrate the argument more rigorously, they just need to look impressively sciency. Economics is currently the most seriously-afflicted discipline, although the other social sciences are rapidly succumbing as massive datasets become available online.

This is nothing new. As their name suggests, the social sciences have been built up by wave after wave of this imitation throughout the 20th century. Or even further back. The scholastic theology of medieval Christianity was largely a centuries-long case of ‘logic envy’. Theologians discovered Aristotelian logic in the 12th century, and proceeded to apply it to the bible in mind-numbing detail.

The indian case is even more interesting. Here the discipline to be emulated was grammar, then far more advanced than any other branch of knowledge (and pretty damn impressive even in a modern context). Grammatical terminology and forms of argument cross over into most other disciplines.